Introduction

We live in unprecedented times. 2025 was the longest 10 years of my life for so many reasons, and major shifts in the real estate landscape here in Greater Boston were certainly a part of that. Later this year Massachusetts voters will cast ballots to decide whether rent control will be implemented for the entire state after two decades since it was repealed by voters in 1994.

As a REALTOR®, it is my responsibility to promote homeownership for buyers and the rights of property owners. That being said, this article is designed to educate voters on the history of rent control in Massachusetts and how it can affect different groups in the market.

Laws and regulations of this magnitude will impact people differently, and it is extremely important to know how you personally would be affected. If you do not have strong feelings about the notion of rent control already, I want to provide an objective outlook so that you can make informed decisions for your own benefit. We will take a look at the history of Massachusetts policy, economic studies, and expert insight. I’ll include my opinion and thoughts at the end.

A Brief History of Rent Control In Massachusetts

It’s nothing new, relatively at least. Massachusetts has a long, contentious history with rent control1, which is marked by repeated cycles of implementation and repeal. The state first experimented with rent regulations during economic shocks, starting in 1920 following World War I and again in 1942 during World War II as the Federal Government under Roosevelt wanted to protect critical supply chain infrastructure. While federal price controls lapsed in 1953, Massachusetts lawmakers extended rent control locally through 1955, aiming to stabilize housing during turbulent times.

The most significant era of rent control emerged in the 1970s, when the state allowed cities like Boston, Cambridge, and Brookline to enforce their own rent regulation systems. These local rent control boards were given strong discretionary power; approving or denying rent increases, even for essential repairs. Over time, critics argued that the policy stifled new development, led to widespread property neglect, and benefited well-connected tenants, including affluent professionals rather than low-income residents. By the early 1990s, only three cities still had rent control, and voters repealed it statewide in 1994 through a ballot initiative brought to the table by landlords who felt they were being taken advantage of by affluent renters that could afford market rates. Cities like Boston, Brookline, and Cambridge were concerned that rental laws in their respective cities could be controlled by voters that lived all over the state.

Since then, attempts to bring rent control back, either through legislation or local efforts, have been fiercely debated and consistently blocked. However, as housing costs have soared across the Commonwealth, a 2026 ballot initiative2 now proposes a strict statewide cap on rent increases, potentially reshaping this century-old conversation once again. The ballot initiative received nearly 50,000 more signatures than required to make it on the official ballot for this coming election cycle, signally strong and unified support for the idea.

Why We’re Here

We are in a housing crisis and have been for quite some time. As simply as I can state it, there are far more people looking for homes than we have available. From my perspective the lengths at which my home buying clients have to go to put a home under agreement has become more costly and more risky. A problem that has become more and more exacerbated during my 15 plus years in the industry.

My grandfather, a phenomenal real estate professional in his career, had always taught me that the middle class not being able to purchase homes would be catastrophic. Unfortunately, we’re at this point. First time home buyers I have traditionally worked with averaged in age from their mid to late 20s and are now closer to 40. It’s taking longer and costing more money. It’s a societal problem that is way more complicated and above my pay grade to manage.

While I don’t personally have a one-size-fits-all answer to solving the housing crisis, I did spend years working in PropTech to develop a platform that allowed home buyers to shop for homes based on their monthly budget. Housing affordability is important in my world. As the cost of living rose just as quickly as housing prices, I often wonder how anyone is surviving financially. It’s so profound that Governor Healy has created a comprehensive housing plan to address the problem3, results to be determined. The State has a strong understanding of what the problems are, stating that 222,000 homes need to be produced to slow housing costs enough that wages can catch up. Housing stock has been negatively impacted by climate change, deed restriction expiration, year-round units converted to short-term leases, and zoning restrictions. A Home For Everyone, is a plan that deserves more attention. It is a profound example of problems being identified with realistic solutions to solving them over the long-term. It won’t be easy, and the administration makes note of the challenges.

Summary Of Ballot Initiative

Summary of the 2026 Rent Control Ballot Initiative

Purpose

The stated goal of the initiative is to provide housing stability and reduce displacement across Massachusetts by limiting how much landlords can increase rent each year.

Who It Applies To

The policy applies to most residential rental units statewide, with a few key exemptions:

- Owner-occupied buildings with four or fewer units

- Units already regulated by a public housing authority (tenants with mobile vouchers are not considered exempt)

- Short-term rentals leased for less than 14 consecutive days

- Units in nonprofit, religious, or educational housing

- Newly built units (less than 10 years old), which are exempt for their first 10 years after receiving a certificate of occupancy

Rent Increase Limits

Annual rent increases are capped at the lower of:

- 5% per year, or, the annual change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- The cap applies even if the tenant moves out and a new tenant moves in (i.e., vacancy does not reset the rent)

- The rent level in place as of January 31, 2026 becomes the baseline (or the most recent rent charged for vacant units)

- If a unit hasn’t been rented in five years or has no rent history, the first post-2026 rent becomes the baseline going forward

Compliance Requirements

For exempt units, landlords must provide tenants with written notice of exemption:

- With the lease (for written agreements)

- Or before the first rent payment (for tenants-at-will with no lease)

Enforcement and Penalties

- Violations are treated as unfair and deceptive practices under Massachusetts consumer protection law (Chapter 93A)

- Tenants may pursue legal remedies under Chapter 93A, including damages

- The Attorney General may also take enforcement action, including civil penalties and injunctive relief

Other Considerations

The measure does not change or override any existing state or federal tenant protections

Initiative Petition For A Law

Below is the full text of the petition, formatted from its original document on the State’s Ballot Initiatives website.

An Initiative Petition to Protect Tenants by Limiting Rent Increases

Be it enacted by the People, and by their authority:

The General Laws are hereby amended by striking out chapter 40P and inserting in place thereof the following:

CHAPTER 40P. LIMITING RENT INCREASES4

Section I. Purpose.

The purpose of this act is to provide housing stability for tenants, landlords, and communities across the commonwealth, and curb displacement as a result of the housing shortage and affordability crisis in Massachusetts.

Section 2. Definitions.

For the purposes of this chapter “covered Dwelling Units” shall mean all dwelling units leased for residential, but not commercial, use, except:

(a) Dwelling units in owner-occupied buildings with four or fewer units.

(b) Dwelling units whose rents are subject to regulation by a public authority; provided, however, that occupancy by a tenant with a mobile housing voucher does not constitute being regulated by a public authority.

(c) Dwelling units that are rented primarily to transient guests for a period of less than 14 consecutive days.

(d) Dwelling units in facilities operated solely for educational, religious, or non-profit purposes.

(e) Dwelling units for which the first residential certificate of occupancy is less than 10 years old, for a period of 10 years from the date at which such certificate of occupancy was issued.

Section 3. Rent increase limits.

This chapter shall establish a limit on any annual rent increase for a covered dwelling unit in the

commonwealth, which shall not exceed the annual increase in Consumer Price Index or 5%, whichever is lower, in any 12-month period. This limit shall apply whether or not there is a change in-tenancy during the relevant 12-month period.

For purposes of this chapter, the rent amount in place on January 31, 2026, shall serve as the base rent upon which any annual rent increase shall be applied. If a covered dwelling unit is vacant on the date of adoption, the last rent amount charged shall serve as the base rent. If there was no previous rent amount, or if no rent has been charged for at least the previous five years, for a covered dwelling unit the rent amount the owner first charges following the date of adoption shall serve as the base rent. Where dwelling units are exempt, a notice of exemption must be provided with the lease for all tenancies. If there is no written lease for such dwelling units, the tenants-at-will must be provided with a written notice of exemption prior to the acceptance of the initial rent payment.

Section 4. Penalties.

Any violation of this chapter shall be deemed an unfair and deceptive act under chapter 93A of the General Laws. Any person claiming a violation of this chapter may pursue remedies under section 9 of chapter 93A. The attorney general is hereby authorized to bring an action under section 4 of chapter 93A to enforce this provision and to obtain restitution, civil penalties, injunctive relief, and any other relief awarded pursuant to said chapter 93A.

Section 5. Interpretation of This Chapter.

Nothing in this section shall be construed to interfere with any existing rights or protections afforded to tenants under current state or federal law.

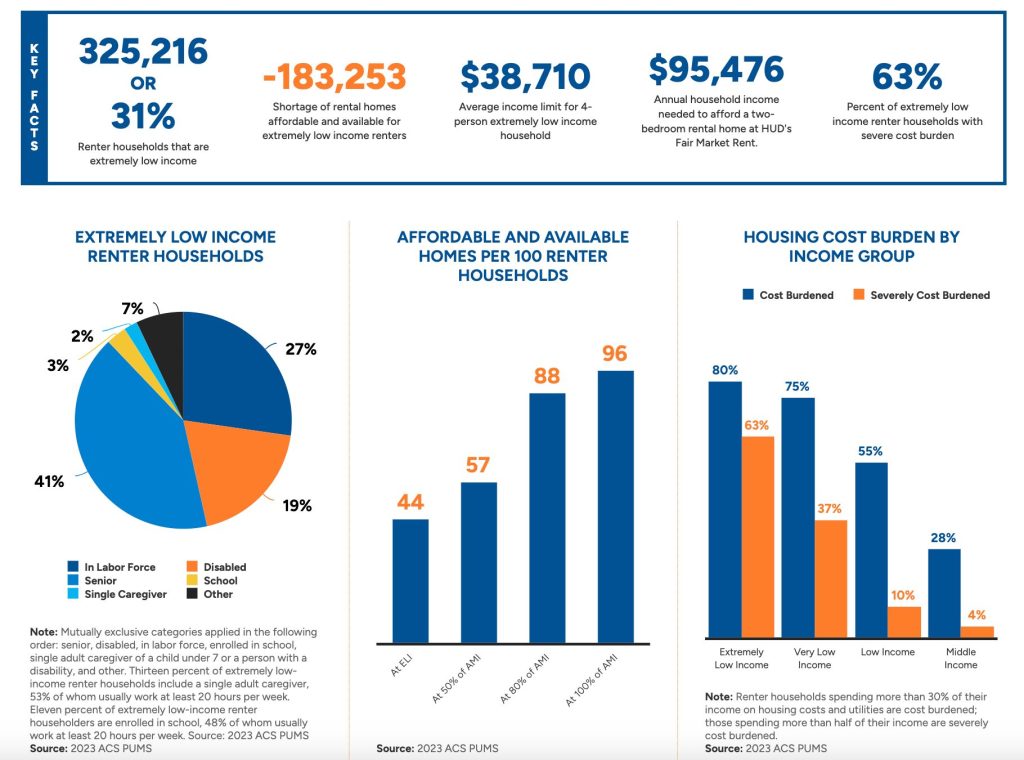

According to Rent Cafe5 via The Cost of Living Index published by the Council for Community and Economic Research (C2ER), rent in Massachusetts is 48% higher than the national average.

What Do Economists Say About Rent Control?

The short answer is that there are a lot of factors and a situation that are hard to measure when often additional policies affect pricing. What I have learned from researching the topic of whether or not rent control is good policy or bad policy is that there is so much nuance. Many economists say long-term rent control does not solve a housing affordability crisis6. It can actually exacerbate the supply problem. What rent-control policies can help with is the displacement of low-income households, something it can be extremely effective at, which I find notable and an important facet to consider. The root-cause of the housing crisis is supply, and with more people needing to rent than currently renting, economists push for relaxation to zoning laws and regulations that prohibit new development. I have noted consistent messaging through various studies that credit rent control’s short-term benefit with immense tradeoffs down the road.

A paper published by Economist Konstantin Kholodilin7 with the German Institute for Economic Research concludes that while the policy measure appears effective for households in controlled units, it comes with undesired effects that equate to higher rates in uncontrolled units, lack of mobility, and reduced residential construction. Kholodilin also notes that other regulations, policy, and external economic factors will complicate the outcome and evaluation of a policy’s perceived success.

An Interesting Note About Rental Inventory In Our Market

2025 saw an interesting change in Greater Boston’s rental market, at least for the communities I primarily serve. In April of last year a few dozen international students at local universities had their visas revoked. Massachusetts has roughly 450,000 international students, contributing $4B to the local economy in 20248. That’s almost 1 in five students, with Massachusetts hosting the 4th largest international student population in the country. Nationally, studies have shown that international students are now avoiding the United States, with a 6% drop in enrollment for undergraduate programs, and 19% for graduate students respectively9.

With college students representing a huge portion of the leasing population in the area, how will that impact rental rates and the real estate market as a whole? Anecdotally, rental inventory has been up on the Multiple Listing Service (MLS), and our apartments have been more difficult to lease. Condominiums that have previously been attractive options for investors have also seen a decline in demand in some cases. Either way, we have seen repercussions from this shift in National Policy.

Annecdotal Observations

A story I often hear from my network, and especially from those renting are situations in which a tenant is informed that their rent is being raised significantly. They find a new place at a predictably higher cost but lower than their current residence, and move out to discover that their original unit was listed at $100 higher than what they were paying. An increase the tenant would have been willing to pay. Other times, I hear of decrepit college apartments that don’t need to be maintained due to their scarce supply and students that need an apartment for only one year. My contractors have shared horror stories of some of the safety issues they have encountered. I hate this about our apartment sector.

The rental industry, especially here in Greater Boston is dysfunctional. I haven’t even mentioned the rampant discrimination that has occurred and how easy it is when tenants do not have advocates on their side. That is a discussion that deserves its own article. For these reasons as well as sky-rocking costs I am all ears to potential solutions to fix the myriad of problems that tenants face. I represent their interests as well as landlords.

I fully support sound policy and protections from disadvantaged groups. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a bigger advocate of Fair Housing Laws in our marketplace, a cause I am fervent about. While My personal opinion may not matter in the grand scheme of things, I’ll provide what I like and dislike about the ballot initiative. Maybe it helps you understand a different perspective than your own.

What I Like About The Ballot Initiative

Like an effective protest, it turns heads. Sure, it may be extremely controversial any way you slice it, but it’s presented by people that want to accomplish something positive that helps people. I celebrate that. Instead of buying into the system, one that is clearly failing, awareness has been raised and there can be conversations. Perfectly sound or an idea so crazy it would never work, I want to hear it and I applaud the effort. There are people struggling out there and I’m all for protections for those groups. Some of you may disagree with the sentiment, and that’s more than okay too.

Where The Ballot Initiative Needs Improvement

While the intentions behind the proposed rent control measure are understandable, protecting tenants from steep increases during a housing crisis, the policy, as written, doesn’t address the root cause of the problem: a lack of housing inventory. Nor does it have the ability to on its own. Without working in tandem with a plan to meaningfully increase the supply of available units, we risk applying a short-term fix to a long-term structural issue.

Rent control may offer immediate relief for some, but it can unintentionally create new challenges for others, especially small-scale, independent landlords. I work with many of these “mom and pop” owners who rely on a single rental unit, often a condo, as their retirement plan. Unlike corporate investors, they typically avoid frequent rent hikes, opting instead to prioritize long-term, respectful relationships with their tenants. For landlords who have kept rents stable for years, a blanket cap on increases, even after a long-term tenant vacates, feels disproportionately punitive.

Policy should aim to balance the needs of tenants and property owners alike, and in this case, I worry the pendulum may swing too far in one direction as we have seen historically. If we want to create a healthier housing market, we need solutions that expand access, encourage responsible ownership, and promote long-term affordability, not just freeze pricing in place. That starts with building more homes, not just regulating the ones we already have.

Is There An Alternative?

What about options such as short-term rent control fixes for a couple of years, subsidies for those that need help the most, tax breaks for landlords that do not increase their rents on an annual basis, etc.

Again, I am the wrong person to provide the solution, but an agreeable one will likely require leaders from different interest groups coming together to form an amiable solution. If that’s even possible.

In Final Thought

It was rewarding to take a deep dive into some of the data and history behind the rent control policy. Especially since its not a side of the industry I spend the most amount of time in. The challenge I see with any sort of policy change is that for many of the groups that would be affected, or seeking relief for that matter, are immensely challenged one way or another. While I’ll stop short of encouraging a vote one way or another this fall, My hope is that I have presented enough information for the reader to either; invest more time in understanding the issue, or providing a different perspective that can create meaningful conversation.

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link